We are in the midst of a new industrial revolution. These are never comfortable, but they do bring about huge increases in economic wealth. The current industrial revolution is being driven by advancements in artificial intelligence, robotics, genetic engineering, and big data (Schwab (2017), Brynjolfsson and McAfee (2014)). One sector of the economy sure to be impacted by automation is the labor market. Millions of jobs worldwide will be displaced by automation in coming decades. However, it is possible that millions more will be created, as productivity gains raise income. Rising income, in turn, generates increased demand for labor across all industries and occupations. Further, new technologies will create new occupations and industries, which will generate new jobs. If that happens, it means that the current industrial revolution will be like many of those we have experienced in the past.

The primary impact will be reallocations of workers across occupations, with new jobs requiring more and/or different skills than the jobs being eliminated. This will place the education system at the center of the adjustment mechanism, smoothing the transition of workers from one occupation/industry to another, as well as producing new graduates with the right skills to work increasingly with robots and artificial intelligences.

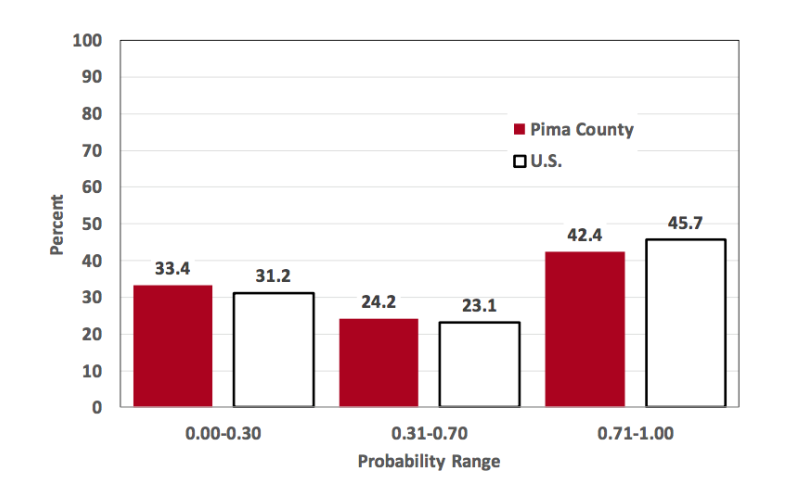

What does this mean for Pima County? Overall, the coming wave of automation will have significant impacts on labor markets globally, nationally, and locally. While there is good reason to expect that net job gains will continue in the aggregate, there is no doubt that significant labor market disruptions are coming. Indeed, drawing on national estimates of the probability of automation for detailed occupations generated by Frey and Osborne (2013), we calculate that there may be 154,458 jobs at high risk of automation in Pima County during the next decade or so. High risk is defined as a probability of automation greater than 70.0%. As Exhibit 1 shows, that translates into 42.4% of all local jobs in 2017, slightly below the national share of 45.7%.

Exhibit 1: Pima County and U.S. Employment Shares in 2017 by Probability of Computerization

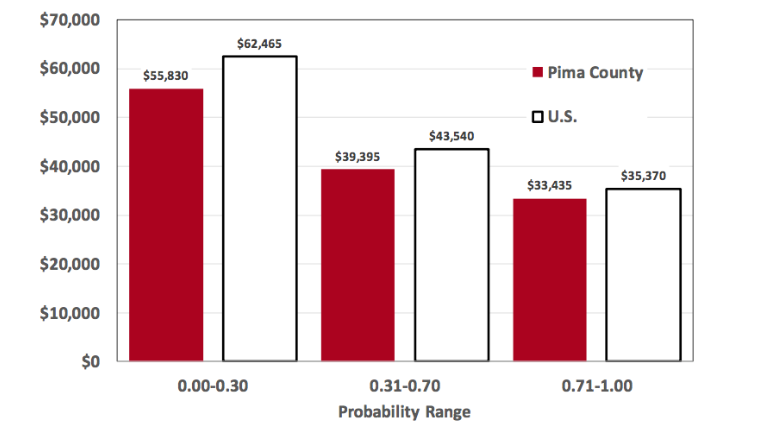

Risks of automation are higher for low-wage occupations than for high-wage occupations. Exhibit 2 shows median wages by probability of automation for Pima County and the nation. Pima County wages are much higher for the low probability group, at $55,830, than for the high probability group, at $33,435. The pattern is similar for the U.S. Note that median wages in Pima County are below the U.S. for each probability group.

Exhibit 2: Median Occupational Wages in 2017 by Probability of Compterization

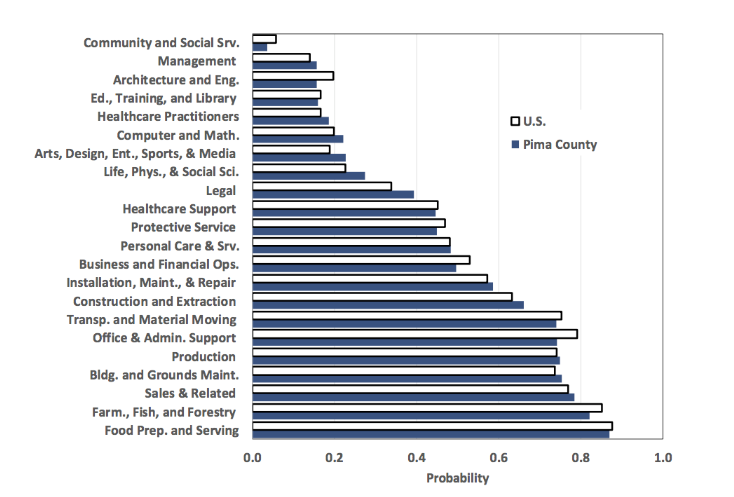

Exhibit 3 shows the probabilities of computerization for Pima County (and the U.S.) by major occupation group. Similar to the nation, food preparation and serving; farming, fishing, and forestry; sales; building and ground maintenance; production; office support; and transportation and material moving had the highest risk of automation. The probability of computerization for each of these occupation groups was above 75.0%.

At the other end of the spectrum, community and social services; management; architecture; education, training, and library; healthcare practitioners; computer and math; artists; and life, physical and social science occupations had relatively low risks of automation. The probability of computerization for each of these groups was below 30.0%. This reflects the high value placed on social and creative intelligence in these occupations.

Exhibit 3: Probablity of Computerization by Major Occupation in 2017 for Pima County and the U.S.

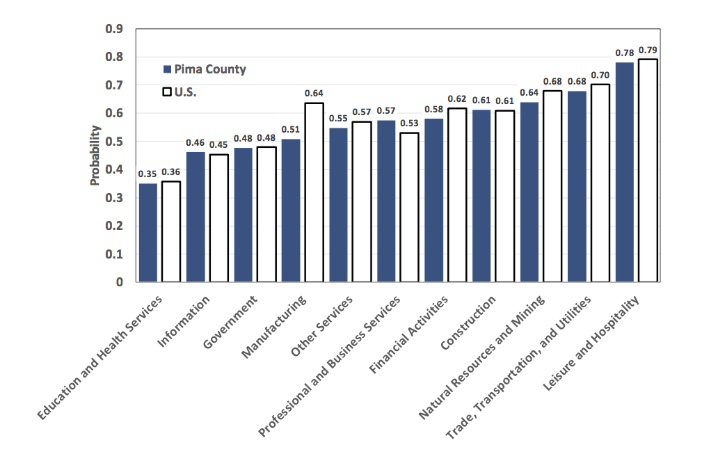

Exhibit 4 shows the probability of computerization for Pima County (and the U.S.) by NAICS industry. Note that the industries with the highest probability of computerization included leisure and hospitality; trade, transportation, and utilities; and natural resources and mining. Each of these industries had a risk of automation above 60.0%. In contrast, education and health services; information, and government had relatively low risks of automation, at below 50.0%. The risk of automation for Pima County automation is well below the national average. That is driven by the local manufacturing occupation mix, which is less dependent on production occupations and more focused on research.

Exhibit 4: Probability of Computerization by NAICS Industry in 2017 for Pima County and the U.S.

It is important to remember that these estimates only consider the job-eliminating effects of automation. There are likely to be powerful positive impacts on job creation as well. Rising productivity will increase income, which will spur additional demand for labor across all industries and occupations. Further, technological progress will create new occupations and industries, which will require workers. We do not know which will dominate on net for any given occupation, or for total employment as a whole. However, McKinsey Global Institute (MGI June 2018) estimate that forces for job creation could outweigh the job-eliminating effects, generating net job growth globally.

Further, the estimates of Frey and Osborne (2013) abstract from trends that might slow the progress of automation in the labor market. If labor is relatively cheap, it will tend to reduce the adoption of labor-saving technology. In addition, regulatory concerns and politics may reduce the adoption of technology, see for example the regulatory and legal issues around driverless cars. As always, note that forecasting is difficult, especially when it comes to the future course of technological advancement.

Frey and Osborne (2013) also abstract from demographic trends (aging of the baby-boom generation) which will be (or already are) generating labor shortages. In the face of these emerging labor shortages, automation will be needed to keep output growing.

MGI and other researchers emphasize that the impacts of increased automation will require workers to manage and trouble-shoot automated systems. Thus, much of the future workforce will need to be comfortable and capable of working with technology. This will require increased technical skill and education. In addition, creative and social skills will likely become increasingly important in the future.

In particular, MGI (May 2018) estimate that the following skill sets will be in more demand in coming decades: advanced IT skills and programming; basic digital skills, entrepreneurship and initiative taking, leadership and managing others, creativity, and complex information processing and interpretation. Skills likely to be less demand in coming decades include basic data input and processing; basic literacy, numeracy, and communication; general equipment operation and navigation; inspecting and monitoring.

This executive summary was orignally published on Arizona's Economy. For more details see the full report. This research was supported by the Pima County Workforce Investment Board.

View the slides from Dr. Hammond's presentation at the The Future of Work forum.

References:

Brynjolfsson, E. and McAfee, A. (2014). The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies, New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company.

Frey, C.B. & Osborne, M.A. (2013). The future of employment: how susceptible are jobs to computerization? Technology Forecasting and Social Change, 114, 254-280.

McKinsey Global Institute. (May 2018). Skill shift: automation and the future of the workforce.

McKinsey Global Institute. (June 2018). AI, Automation and the Future of Work: Ten Things to Solve For.

Schwab, K. (2017). The Fourth Industrial Revolution, New York, Crown Business